IT is difficult to believe that world leaders once had time for leisurely reading. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt was surely one of the more bookish. Meditating on the intimacy that can exist between readers and their books, Roosevelt once asserted that ‘If a man or a woman is fond of books he or she will naturally seek the books that the mind and soul demand.’ Roosevelt was a demanding reader and books seem to have been for him one of the necessities of life, wherever he found himself.

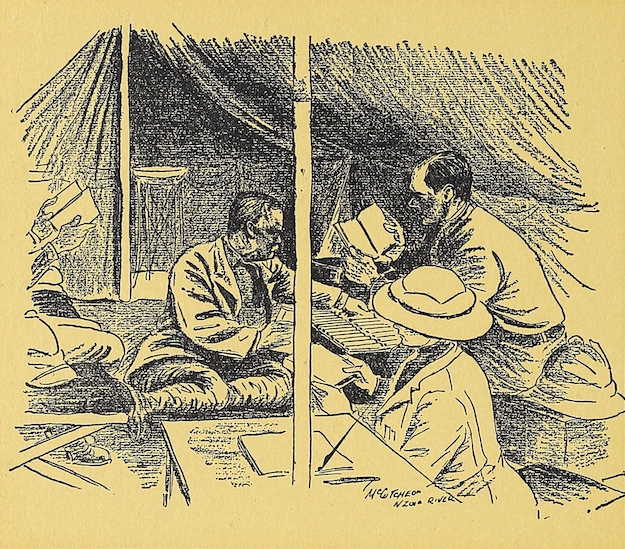

Between 1909-10, he traveled as a member of an African expedition on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution. In preparation for the mission, his sister, Corinne, commissioned for her brother an extensive traveling library. To be housed in a bespoke aluminum box, over 50 volumes were carefully chosen before departure. Protected from the tropical climate, wrote Roosevelt, and the ‘blood, sweat, gun oil, dust and ashes’ of safari, the volumes were bound in custom pigskin which he later observed ‘grew to look as a well-used saddle looks’. His attitude to his portable library was nothing if not pragmatic. It had to be light enough, he remarked, to allow a porter to handle and in the rebinding process, blank leaves were removed and the margins trimmed to reduce their weight.

An early inventory of ‘The Pigskin Library’ was published in Roosevelt’s account of the mission, African Game Trails. As well as canonical works such as the Bible and Shakespeare, poetry was represented in anthologies of Tennyson, Browning, and Shelley. Lighter works included Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, no fewer than 5 novels by Walter Scott, and Dickens’s Pickwick Papers and Our Mutual Friend. He seems to have been particularly fond of the works of George Borrow, five of whose novels accompanied him to Africa. At the more serious end were Carlyle on Frederick the Great, Gregorovius’s History of Rome, and Bacon’s Essays.

Throughout his life, Roosevelt was an advocate for the individuality of reading. From Khartoum in 1910 he reflected on the Harvard Classics, the ‘five-foot’ series of great books that had been inaugurated in the previous year. The merits of the Bible and the works of Shakespeare, Homer, and Dante, he remarked, were in no doubt. ‘Mr. Eliot’s list is a good list’, he continued, but it was impossible to make ‘any list of the kind which shall be more than a list as good as many scores or many hundreds of others’. What he really objected to was the Harvard President’s idea of a fixed canon, giving no account of the variety of individual tastes, historical changes, and cultural and geographical difference.

A voracious reader, the 26th President of the United States was sure to keep reading matter on hand throughout the rest of his life and, as time passed, his book acquisitions became ever-more extensive. Later he described his domestic library on Long Island:

The books are everywhere . . . . There are as many in the north room and in the parlor—is drawing room a more appropriate name than parlor?—as in the library; the gun room at the top of the house, which incidentally has the loveliest view of all, contains more books than any of the other rooms; and they are particularly delightful books to browse among, just because they have not much relevance to one another, this being one of the reasons why they are relegated to their present abode. But the books have overflowed into all the other rooms too.

From the intensive relationship that he had with his treasured box collection in Africa, to the assurances he found as he walled himself around with his later domestic library, Roosevelt is an important example of the generations of Crusoe’s successors whose intimate relationship with books has been a source of mental sustenance, wherever they might have found themselves.

The Pigskin Library, now comprising 55 volumes, is today preserved in the Houghton Library at Harvard.

2 thoughts on “Roosevelt’s Pigskin Library”