THROUGHOUT the transportation period, a number of gentleman convicts (referred to as ‘Specials’) made their way to Australia providing evidence of the vast range of literacies and competencies among the prison population. One class of prisoner, set apart from the ordinary criminal, was those serving out sentences during the periods of Fenian unrest in Ireland.

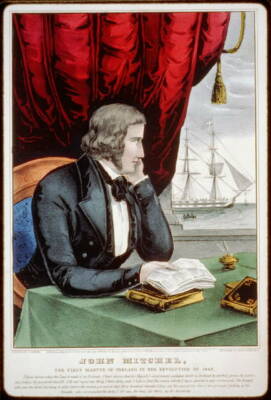

John Mitchel (1815–75), the son of a Presbyterian clergyman, entered Trinity College, Dublin at the age of fourteen. By 1845 he had earned himself notoriety as a journalist on the staff of the republican Nation and for his associations with the Young Ireland Movement. Three years later he inaugurated The United Irishman, where his editorials advocating armed struggle in the cause of Irish independence brought him to the attention of the British authorities. A central figure of the rebellion that year, he was arrested for ‘Treason-felony’ and consigned first to Spike Island, then Bermuda, and finally to Van Diemen’s Land, from whence he escaped to the United States to continue his career as a political journalist and editor.

The early weeks that he spent in custody ‘were passed in relative comfort’. On his arrival at the Dublin docks he was treated as a celebrity: awaiting his departure he signed autographs for the guards and was given preferential treatment and a single cabin. On his way to Spike Island he dined with the captain, several of the officers loaned him books, and the guards slipped political newspapers under his door. At Bermuda his cell was provided with two bookshelves, which the chaplain offered to furnish, and he was allowed ‘to receive any books I please from home’.

W. B. Yeats called Mitchel ‘the only Young Ireland writer who had a style at all’. Today the block at the Irish fortress prison on Spike Island, where he was held for only two days, is named in his honour. His Jail Journal is full of references to the many titles that he encountered on his way south and the responses they provoked. Mitchel is anything but a passive reader. He uses books deliberately to generate ideas: ‘One feels the value of even a very bad book,’ he wrote, ‘of anything, in short, that will help imagination and memory to take the place of the senses and of human converse, furnishing occasion and stimulus for thought.’ He is also one of the most situational of readers, passionate in his responses, using texts as stalking horses for his hatred of the British state and its colonial agents. Reading Macaulay’s Essays sets him off on a ‘ten pages. . . tirade’ and Alexander Burnes’s Travels in Bokhara leads to a seven-page attack on the abuses of British foreign policy in the East.

Having access to newspapers from Britain and Ireland affords him an opportunity to keep up with the fortunes of his fellow Fenian conspirators and, at the same time, to write long and passionate attacks on Britain’s geopolitical relations. At several points he remarks on the echo chamber of patriotic British journalism, bemoaning the fact that he has no access to the counter-narratives of the contemporary French press.

At times, Mitchel’s diary functions as a commonplace book, and is peppered with quotations from poetry–from Byron to Scott, Moore to Shakespeare–which he takes as relevant to his situation. The quotation of Ovid, Plato, and the Bible in classical Greek are among examples of what we might call conspicuous literacy, a rhetorical strategy that the disenfranchised educated classes often used to signal their resistance to those they regarded as lesser-educated authorities.

The Jail Journal is a highly performative piece of writing full of defiance and intellectual display. Mitchel’s command of languages ancient and modern and his high cultural repertoire are constantly apparent. Most contemporary British fiction, he sneers, would not satisfy ‘the loneliest captive, in the dullest jail, dying for something to read’. Some of the titles he comes across are ‘such offal that there is no use in . . . remembering their names’. More to his liking than the lowbrow taste of his captors are Shakespeare, Rabelais, Carlyle (his hero), and Plato, whose Politics he sets out to translate in captivity. Mitchel’s writing, and his many remarks about his prison literature, show him to have been a complex, sometimes contradictory, but always engaged reader.

While he has long remained a hero to those who have sympathized with the Fenian cause, in recent months the contrarian Mitchel has come in for some severe criticism: his views on slavery and his support for the Confederacy during the Civil War, have led to a recent revaluation of his influence in the wake of the BLM movement. Nevertheless, the Jail Journal, written before his entanglement in American politics, continues to be one of the most detailed and compelling accounts of the mentality of a gentleman prisoner in the period.