GUEST BLOG: Dr Lauren Alex O’Hagan, Örebro University/The Open University

AN 1870 COPY of The Keepsake Scripture Textbook has sat on my bookshelf for years. I picked it up in a second-hand bookshop in Bristol for far more than it was worth out of pure fascination for the inscriptions on its front endpapers. I was haunted to find out who Louisa Rimmer and Cousin Edith were, and what on earth had happened to poor Bertha Dupré.

Through a deep delve into archival records, I was able to discover that Bertha was the daughter of an assistant draper and lived in Altrincham, Cheshire with her parents and four siblings. She suffered from a chronic digestive disorder and, at the start of 1886, fell ill with abdominal pains, loss of appetite and constipation. Just over one week later, she slipped into unconsciousness and passed away in her bed with her father Thomas at her side. She was just 16 years of age. The attending doctor, W. J. Jones, declared her cause of death to be “obstruction of bowels,” which had led to a “syncope”— something that medical historians agree was likely to be a fatal flare-up of Crohn’s disease (not formally diagnosed until 1932). When clearing out Bertha’s belongings, sister Edith came across The Keepsake Scripture Textbook, which she had given to Bertha on her 11th birthday. She decided to reinscribe it to her 16-year-old cousin Louisa Rimmer “in remembrance” of Bertha.

The tragic tale of Bertha Dupré deeply moved me, and I began to hunt for more and more in memoriam inscriptions from the long nineteenth century to build my collection. Over time, I was intrigued to discover that they were almost all written by working and lower-middle class individuals. Could the in memoriam inscription be a uniquely lower-class practice? This was something that I set out to explore in my recent article for Textual Cultures.

The Materiality of Death and Mourning

Deborah Lutz describes the body and the book as interconnected: on a literal level through hidden relics (e.g. locks of hair, cremation dust) hidden between the pages, but also on a metaphorical level through inscriptions that fossilise moving life into static representations. While Bibles had been used since at least the 16th century to mark births and deaths, a significant change began to take place in book culture in the Victorian era in response to the growing cult of mourning. Owners increasingly recognised the blank endpapers of their books as safe spaces to impart private musings on illness, death and grief.

These musings were initially limited to those with a certain level of literacy and the financial means to afford a book. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, the democratisation of education and book ownership meant that such practices were just as likely to be carried out by the working and lower-middle classes. For these groups, the in memoriam inscription became a popular way to transfer book ownership in death, while also memorialising the life of the deceased. It, therefore, offers a unique window into how the working and lower-middle classes developed their own customs of dealing with death, transferral of property and relationship rituals.

In memoriam inscriptions were written from one family member to another who acted as a mediator, marking the book “in memory of” or “in remembrance of” the deceased. The book was often carefully selected because of its connection between the two people (e.g., shared taste in author or genre, shared memories surrounding its purchase or reading), but it could also be given simply as a stand-in for the person themselves regardless of its content. Through in memoriam inscriptions, books were turned into “contact relics” that “persistently called the dead into the sphere of the living,” which granted them symbolic meanings disproportionate to their everyday value. Thus, they served as a meeting point between life and death, materiality and selfhood, body and personality, enabling the bereaved to adapt to their loss yet maintain a relationship with the memory of the person.

Memorialising the Young

The above inscription marks the death of 12-year-old David Stewart. David was born in 1892 in the slum district of Fountainbridge in Edinburgh and, since the age of seven, had suffered from pseudo-hypertrophic muscular paralysis—a genetic muscle-wasting disease that is known today as muscular dystrophy. In December 1903, he caught tuberculosis—a “fundamental destructive social force” for which there was neither cure nor prevention—and passed away just two months later.

Shortly after David’s death, his sister Beth found the book Helps Heavenward amongst his belongings. She subsequently inscribed the endpapers “in memory of” David, noting that he died on 25 February. Her raw emotion is captured in the heavy underlining of the inscription and insertion of “dear” next to David’s name. On the one hand, being a material object that belonged to the deceased, the book carries its own “aura”[7] which tells a history of the hands that have touched it. Yet, on the other, the new inscription added to the book acts as a frame in the process of loss, signalling the lingering presence of David yet moving him into a new relationship with his sister.

Memorialising the Elderly

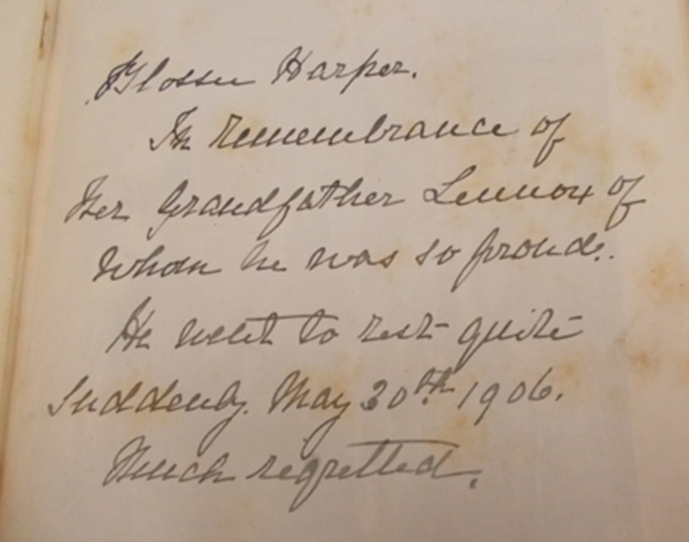

Behind this inscription lies yet another sad story, this time of William Marshall Lennox—a former printer and Calvinist Minister who lived in Cardiff with his wife Lucretia. On the evening of 30 May 1906, William left his house at 54 Connaught Road and walked to nearby Newport Road to catch a tram to Cardiff Central Station. He was planning to take the 22:30 train to London as he had a meeting early the next morning with the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. As he reached the corner of Oakfield Street, William fell to the ground suddenly in a fit. An onlooker, Mr. Newbury, immediately flagged down a passing police constable and, together, they carried William to the house of Councillor Kidd who lived just a few doors away. Drs Phillips and Campbell were summoned and pronounced William dead on arrival. The autopsy revealed that he had suffered from a fatal heart attack.

Following William’s death, wife Lucretia sorted through his personal possessions and discovered a copy of The Great Composers by C. E. Bourne. Knowing that their granddaughter Flossie shared a great love for music with William, she inscribed the book to her “in remembrance,” adding that her grandfather was “so proud” of her and that he “went to rest quite suddenly,” which was “much regretted.”

***********

Through the examples of Bertha Dupré, David Stewart and William Marshall Lennox, we see how the in memoriam inscription stands as an important example of how people managed loss and maintained relationships with their deceased loved ones throughout the long nineteenth century. It particularly challenges the belief that the lower classes had an attitude of fatalism towards death and emphasises that, even though their public lives may have required them to be pragmatic or even stoic, they were by no means indifferent and showed their grief within the private sphere.

Despite its frequent use throughout the Victorian and Edwardian era, the in memoriam inscription experienced a sharp decline in inter-war Britain, perhaps in response to World War One’s “normalization” of death, as well as increased secularism, falling mortality rates and rising life expectancy. Added to this was the expansion of will-making across the working and lower-middle classes, which may have lessened the need for in memoriam inscriptions to transfer book ownership, and the replacement of letter-writing with telephone calls, which left no written trace.

When in memoriam inscriptions were used, they became shorter and less soliloquised, with the use of death dates and crosses occurring far more frequently than fervent appeals “in memory of” or “in remembrance of.” In memoriam inscriptions from the 1930s and 1940s also indicate a clear transition towards the mourning of public figures (e.g., King George V, Neville Chamberlain) and even include newspaper clippings, poems and photos, suggesting an evolution towards parasocial forms of grief that were seen as less taboo.

Surviving in memoriam inscriptions thus represent an important source on people’s experiences of illness, death and grief and offer the opportunity to access the voices of many of those whose experiences might not otherwise be heard. It is therefore important to grant them equal significance to other relics of death, such as hair jewellery and memorial cards, and preserve and research them to keep these individuals’ stories alive and prevent them from becoming “dead letters of the object world.”

Lauren Alex O’Hagan is a Research Associate in the School of Languages and Applied Linguistics at the Open University and a Visiting Postdoctoral Researcher in the Department of Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University. She specialises in performances of social class and power mediation in the late 19th and early 20th century through visual and material artefacts, such as book inscriptions, food advertisements and postcards. Her monograph The Sociocultural Functions of Edwardian Book Inscriptions was published by Routledge in 2021.