TODAY the ability to store hundreds of books on a tablet or an e-reader has removed many impediments to far-flung reading. These days, anyone who has access to a mobile phone connection can download an infinite number of titles far from home. But in the past, the itinerating library, aimed mostly at the well-heeled traveller, was one solution for reading on the road.

Innes Keighren has written in a previous article about the libraries that accompanied explorers in the nineteenth century. In another item we looked at the ‘pigskin library’ that Teddy Rooseveldt took with him to Africa in the 1920s. But the travelling library has much earlier beginnings. Alberto Manguel reminds us that ‘Alexander famously kept by his army bedside a copy of the Iliad to give his campaigns classic lustre; almost a couple of millennia later Thomas Jefferson did the same. Both men,’ Manguel goes on, ‘imagined that Homer’s heroes would inform and justify their political campaigns.’

Two Seventeenth Century Examples

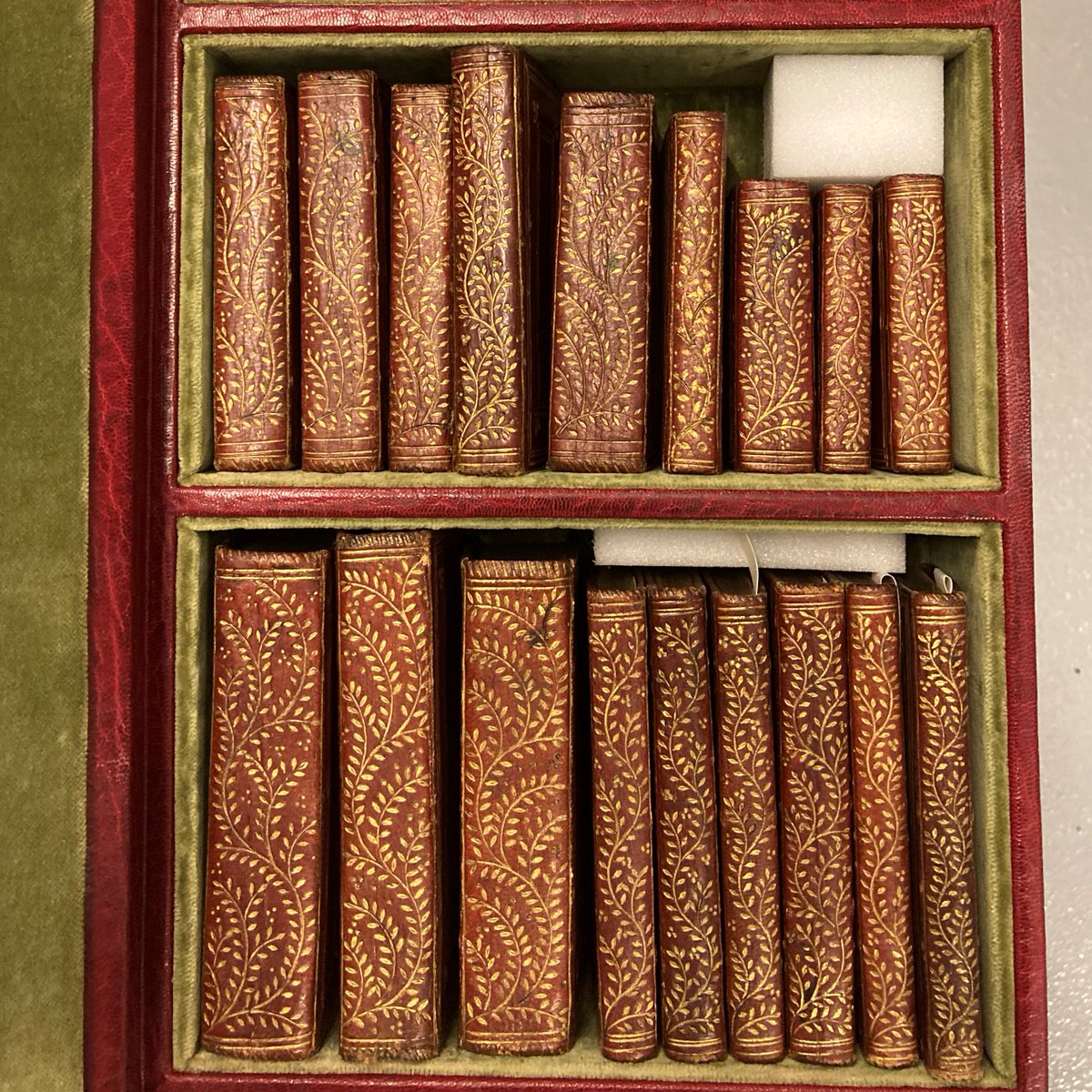

In The Tempest Shakespeare has Prospero confess that he prized his library above his dukedom and has the faithful Gonzalo provide his exile with reading matter far from home. There is plenty of evidence such fictional readers had their real-life counterparts throughout the centuries and a number of early examples of the travelling libraries of real readers from the seventeenth century survive. Although there is not much evidence that he used it on the move, Charles I was given a portable trunk library as a child in 1608 (pictured above). Tooled in gold and uniformly bound, the Prince’s collection, which includes a predictable selection of classical authors and standard theological works, is now held in the Bodleian Library.

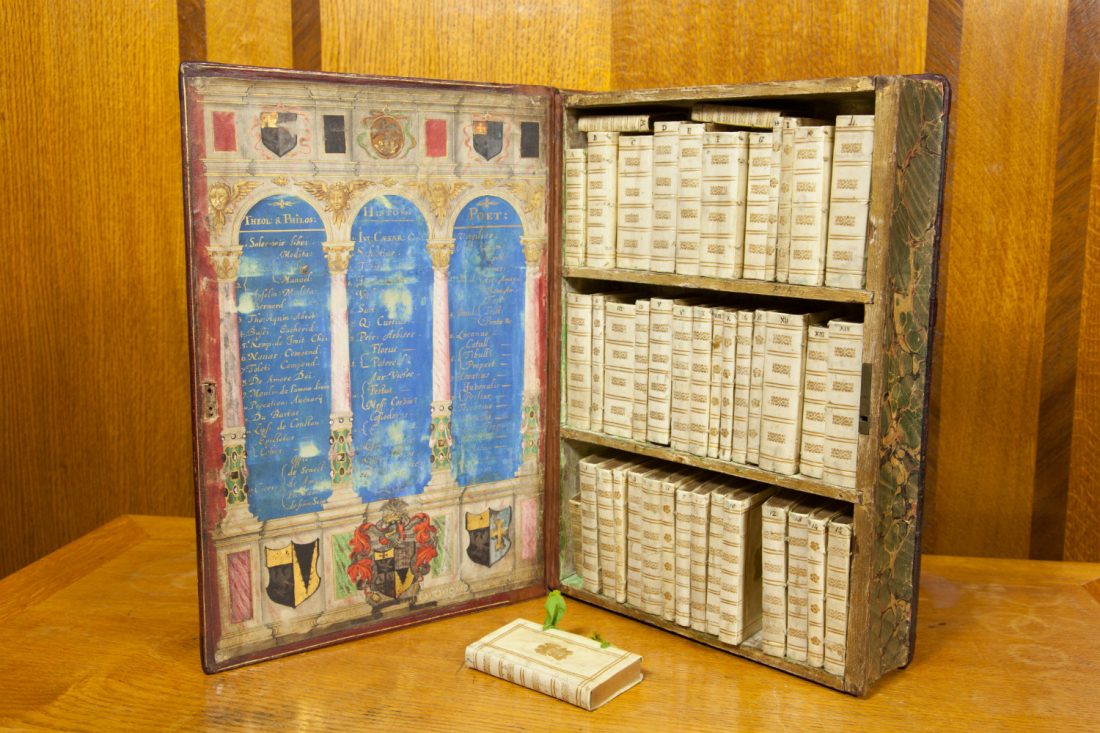

Among the most impressive early examples is William Hakewill’s of 1617. Hakewill commissioned others for his friends of which several survive. A learned Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, he was a friend of the celebrated bibliopoles Sir Robert Cotton and John Bodley. In 1979, Howard M. Nixon identified four surviving examples of box libraries that Hakeswill gave as gifts to his influential associates. In each instance, Nixon found the contents and arrangement ‘approximately the same’. Hawkswill’s own (pictured below) is now held by The University of Leeds, and, like the others, is contained in a book-shaped trunk. Each decorative case has the catalogue ornately presented inside, and bears the arms of the recipient. While some of the individual titles are now missing, Nixon was able to provide a full inventory of each library’s catalogue. Given their pedigree, there are few surprises in the collections that Hakewill assembled. The major classics are well represented as are early works of theology, all uniformly bound.

Napoleon’s Campaign Library

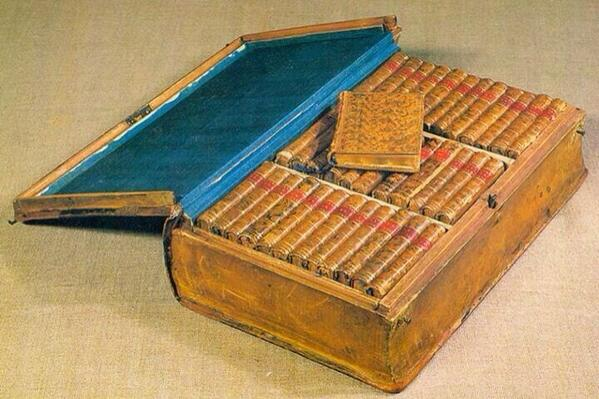

For many of their influential owners, the personal travelling library served as entertainment and distraction from the rigours and boredom of the journey. For others, it was strategically important to the success of the mission. Alexander the Great’s campaign library had many later imitators. Among the most celebrated are the itinerating collections assembled for Napoleon who was a voracious reader with eclectic tastes, ranging from classical history to romance novels. In the year he became Emperor of France, he issued the following order to his librarian:

The Emperor wishes you to form a traveling library of one thousand volumes in small 12mo and printed in handsome type. It is his Majesty’s intention to have these works printed for his special use, and in order to economize space there is to be no margin to them. They should contain from five hundred to six hundred pages, and be bound in covers as flexible as possible and with spring backs. There should be forty works on religion, forty dramatic works, forty volumes of epic and sixty of other poetry, one hundred novels and sixty volumes of history, the remainder being historical memoirs of every period.

During his exile on St Helena, the vanquished emperor found himself with more than enough time on his hands to satisfy his love of reading. Among the titles that he enjoyed the most were the works of Molière, The Sorrows of Young Werther, and Macpherson’s Ossian. In his will, Napoleon bequeathed to his son ‘Four hundred books chosen from my library, among those I used the most.’ Sadly, this final request was never granted and his exile library was auctioned off in London in July 1823.

While, from its origins, the travelling library was associated with the privileged reader, in future articles we will be looking at some modern examples, including commercially produced select libraries for the relatively wealthy traveller as well as more generally available alternatives for the less well to do.

.

Comment:

I was delighted to see Innes Keighren’s piece on expeditionary libraries, particularly that of John Ross. It’s an impressive if too brief list and any polar collector’s dream. I do wonder if there is any evidence that it was selected “under Ross’s direction”? We don’t know enough about the provision of libraries to naval ships, select like this one, or large, like the much larger libraries on Franklin’s HMS Erebus and HMS Terror or the Franklin Search ship HMS Assistance. To me it seems more likely that the books were selected by and supplied through the Admiralty, and only in the sense that a commander is responsible for everything going on in his ship, would Ross be directing the selection. But I’d love to learn more on the subject. (The exception of course was the library aboard Scott’s Discovery, for which the publisher-donor provided a rather full catalogue.)

On the question of portability of single volumes, the best example I know is the Franklin relic of Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield. It was on view a few years ago in museums of Greenwich, Toronto, and Mystic: it appears to be less than four inches high.

Finally, readers might remember the piece I contributed to this blog early on, “A Disabled Reader’s Tale. In it I railed against the difficulties some disabled readers encounter in reading tightly-bound paperbacks that require two or more fists. Today I was amused to find this listing in Wikipedia: Geiger, John. The Third Man Factor: Surviving the Impossible Paperback.

David H. Stam

Senior Scholar

History Department

Syracuse University

Syracuse, NY, 13244

LikeLike

It’s always a pleasure to receive a comment from our erudite reader in Syracuse. You are right to draw attention to the importance of format to portability, one aspect of mobile reading that we will be reflecting on in a future item. Thank you.

LikeLike